This week, UBS Global Research has been in touch with us at DisruptionBanking to share some interesting findings. They have been collating data through their “Question Bank” to determine the most pressing questions their clients in the banking and financial services sector currently have. The answers are particularly worthy of consideration because the Question Bank is, in the words of UBS:

“The largest global database of market-related questions asked by professional investors – over 200k questions across different asset classes, sectors and geographies. It helps professionals in different parts of UBS to identify the most important debates in a timelier, client-centric and scientific way”.

Because of the sheer scope of the database – which spawns “asset classes, sectors and geographies” – the questions offered might, to a large extent, be representative of wider market concerns. What, then, are the five biggest questions on the minds of clients today?

“In the context of ESG in banks, we have seen many scorings done by many parties which becomes very confusing for investors. Would you think there would be a standard ESG scoring that we will all converge to?”

This has been a topic of concern for some time, and is likely to attract even greater attention as a result of recent reports on climate change, such as that of the IPCC. As we covered recently, banks are increasingly being forced to dedicate greater resources to products like green bonds. This can be partly attributed to heightened shareholder activism, as we saw with the recent Exxon Mobil case, and the potential physical risks climate change poses to assets worldwide. UBS, for its part has pledged to “deliver innovative investment products that support impact and socially, responsible themes.” But how is this best done in practice, given the difficulty of measuring an asset’s ESG credentials? Earlier in the year we spoke to Simon Rodda of Dow Jones, who rightly asked a similar question to that of UBS’ clients:

“How do you measure one company against another company on ESG? You cannot simply look at the P/E ratio and say ‘well, this one is better than that one’.”

For this reason, if banks are going to be serious on ESG and investing in sustainable assets, some kind of accepted market standard for ESG scoring should be agreed upon. This is something that the IOSCO is currently working on. Such a measurement will be crucial if we wish to avoid companies overstating their ESG credentials in a bid to benefit from market demand for such products. What form such a scoring would take, and how it would be governed, will of course be a difficult debate to have. But an answer will be crucial in the years ahead, and it seems to be something that the market and clients are demanding.

“Investors can support companies on sustainability issues, but the real agency is with executives.” Read more in this op-ed from @JudySamuelson, where she proposes a better system for measuring ESG. @AspenBizSociety https://t.co/dPQh2Av5wL pic.twitter.com/wp2QSbMzhd

— The Aspen Institute (@AspenInstitute) August 5, 2021

“How will asset managers differentiate themselves and prove they are the right option to invest with in the future? With the increase of financial platforms and the increase in the younger generations’ know-how taken into account.”

It is certainly true that asset managers and financial institutions are trying to grapple with the increased take-up of digital financial platforms by the younger generation. Indeed, digital platforms and challenger banks are becoming an integral part of this generation’s entire lifestyle. They have come to facilitate not only investments, but also offer useful insights on spending and advice on saving. For this reason, they have become an important feature of this generation’s financial management.

Additionally, sagas like that of GameStop have arguably led to a tension arising between the “professional” financial institutions and the individual “amateur” investor – with the latter arguably having won. The fact that it was hedge funds that lost out, which are often considered to be more strategically nimble than big banks, should be another reason for concern. Because of this, asset managers and other institutions will need to prove they can outperform the “Reddit trader.” Increasingly, they will also have to embrace digitalisation and offer the same (or better) services that a whole new generation of fintech start-ups and challenger banks have brought to the market. They will not necessarily be able to rely on their status as established banks, particularly when the new generation shows so little loyalty to the institutions their parents and grandparents used. Realising this reality, and responding to it effectively, will be the key to established asset managers, like UBS, ability to differentiate themselves in the future.

Robinhood’s shares surge in volatile trading https://t.co/mcHoyJOykS

— Financial Times (@FT) August 4, 2021

“What will it take for the US to see a normalization of the default cycle? Will the next cycle be worse because of the extraordinary fiscal support this cycle and the expectation now embedded at both issuers and investors that the Fed/Congress will always step in to support the economy?”

This question reflects a wider concern with the macroeconomic environment, which is hardly surprising as the world emerges from all of the turbulence of the Covid-19 pandemic. The credit cycle consists of two broad periods. The first is defined by funds being easy to borrow, and being available at lower interest rates and with lowered lending requirements. We are in such a period currently. The period that follows is defined by a reduction in the availability of credit, and might conversely be marked by higher interest rates and more stringent requirements. This is because of the higher risk of borrowers defaulting on their payments.

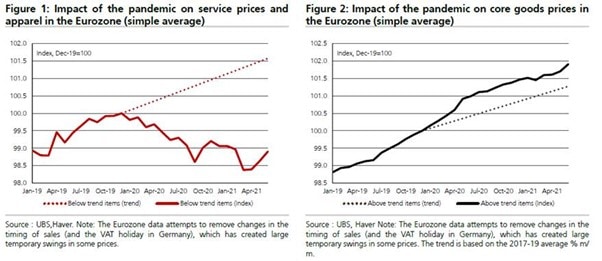

Central banks around the world responded to the outbreak of the pandemic last March with huge quantitative easing (QE) programmes. It was believed that cheap and easy access to cash was essential to support the markets through the pandemic. Whilst, to an extent, this had the effect of stablising the markets over the past year, we are now faced with the issue of increased inflation. For this reason, it now appears that central banks, including the Fed, are erring towards tapering. They are beginning to plan the withdrawal of support, and even show signs of toying with interest rate increases, as part of a “normalisation.”

This will certainly be a jolt to the markets, given the extent of the support we have seen – though both the Fed and the Bank of England have emphasised the gradual approach they will take, in a bid to avoid such a shock. The effect of the last year on future default cycles remains to be seen. Certainly, given the responses to both the 2008 financial crash and the Covid-19 pandemic, it seems that a precedent has been set. Markets and financial institutions will now expect governments and central banks to step in to support the economy in future times of difficulty. The question is: how serious will a crisis have to be for central banks to step in? Few will deny that 2008 and 2020 were extraordinary times, but Central Banks will need to avoid a descent into Japan-style endless QE and regain stable, healthy inflation.

“How blockchain brings disruption to financial services? What are the biggest obstacles?”

Blockchain has the potential to disrupt financial services immensely. It is no coincidence that banks have invested billions into the technology, with the International Data Corporation (IDC) forecasting that investments will total nearly $6.6 billion by the end of this year. At a basic level, the power of this technology lies in the fact it can make immediate, digitally-signed transfers of anything virtual. It can also do this with barely any running costs. In this sense, it can inject value into the business and supply chain through its speed and efficiency. The mass adoption of blockchain in financial services arguably faces a major obstacle, however. In finance, trusted third parties have long been essential to practice. The transfer of cash or other assets has always been done via institutions such as banks and clearing houses. Blockchain operates more directly, cutting out the third-party. Whilst this has its benefits in some fields – the transfer of data, for example – it is is unclear whether consumers are comfortable transferring assets directly to each other without the involvement, and oversight, of a trusted third-party. The legal implications of this potential transformation are also unclear. This is perhaps the biggest obstacle to its mass adoption in the short-term.

Nevertheless, blockchain could still disrupt financial services in the near future by cutting costs for consumers through increased efficiency in various back-end operations. Blockchain solutions in the realm of data collection could also help asset managers enhance compliance oversights, reduce regulatory and operational costs, and ultimately provide better outcomes to clients.

Global spending on #blockchain solutions will be nearly $6.6 billion, an increase of more than 50% compared to 2020, according to the IDC Worldwide Blockchain Spending Guide. https://t.co/F70721Zzi4 pic.twitter.com/m8lsFDrWUl

— IDC | Nordic (@IDCNordic) April 21, 2021

“Bank digital transformations and fintech partnerships: In the context of collaboration, who will be responsible for customer acquisition? Is it the Momo of the worlds or does bank have to go out and acquire their own digital customers or their own apps?”

In terms of customer acquisition, we are certainly seeing larger numbers of fintech start-ups and challenger banks achieving impressive onboarding figures. In many respects, this is because the ease of setting up an account with these companies tends to be far easier than opening an account with a traditional bank. A Revolut account can be opened with a mere 24 clicks on the app, compared to First Direct’s 120 clicks. Furthermore, start-ups are allowing customers “to open accounts directly through the app [and] remove the worst parts of the traditional experience.” The requirement for time-consuming (and annoying) data collection is also limited. It would be wrong, however, to suggest that increased clients for such platforms has come at the expense of established banks. After all, many of these platforms simply offer access through their apps to accounts held at other institutions. In other words, their value comes from tidying up and simplifying the existing banking experience, rather than creating a new one altogether. Even those that do offer standalone services, like Starling, are not in a position to offer products such as mortgages despite undoubtedly growing in sophistication. The relationship between banks and fintechs is therefore interconnected, with both requiring the other. Banks, and their clients, will continue to benefit from the innovation and digital transformation offered by emerging digital platforms. Fintechs will need to provide a service to the vast client base of the established banks by improving their banking experience. Their responsibilities overlap.

The findings of UBS Global Research are compelling. They reflect the major concerns of their clients as global economies emerge tentatively from the disruption of the pandemic. The questions posed touch on issues whose answers will define the future not only of UBS or the banking industry, but also the entire global economy in the years to come. If and how these questions are answered by market participants, economic leaders and world politicians will be important for us all.

Author: Harry Clynch

#UBS #ESG #AssetManagement #DigitalBanking #ChallengerBanks #DefaultCycle #Tapering #Inflation #Blockchain #DigitalCustomerExperience

One Response