By David Whitehouse

Could China’s backdown on aspects of its zero-Covid policy in the face of popular protests be a sign of broader changes in society and governance?

While the Communist Party’s grip on power and its ability to draw and enforce red lines remain intact, experts see some reason to believe that life can’t go back to mass unquestioning obedience.

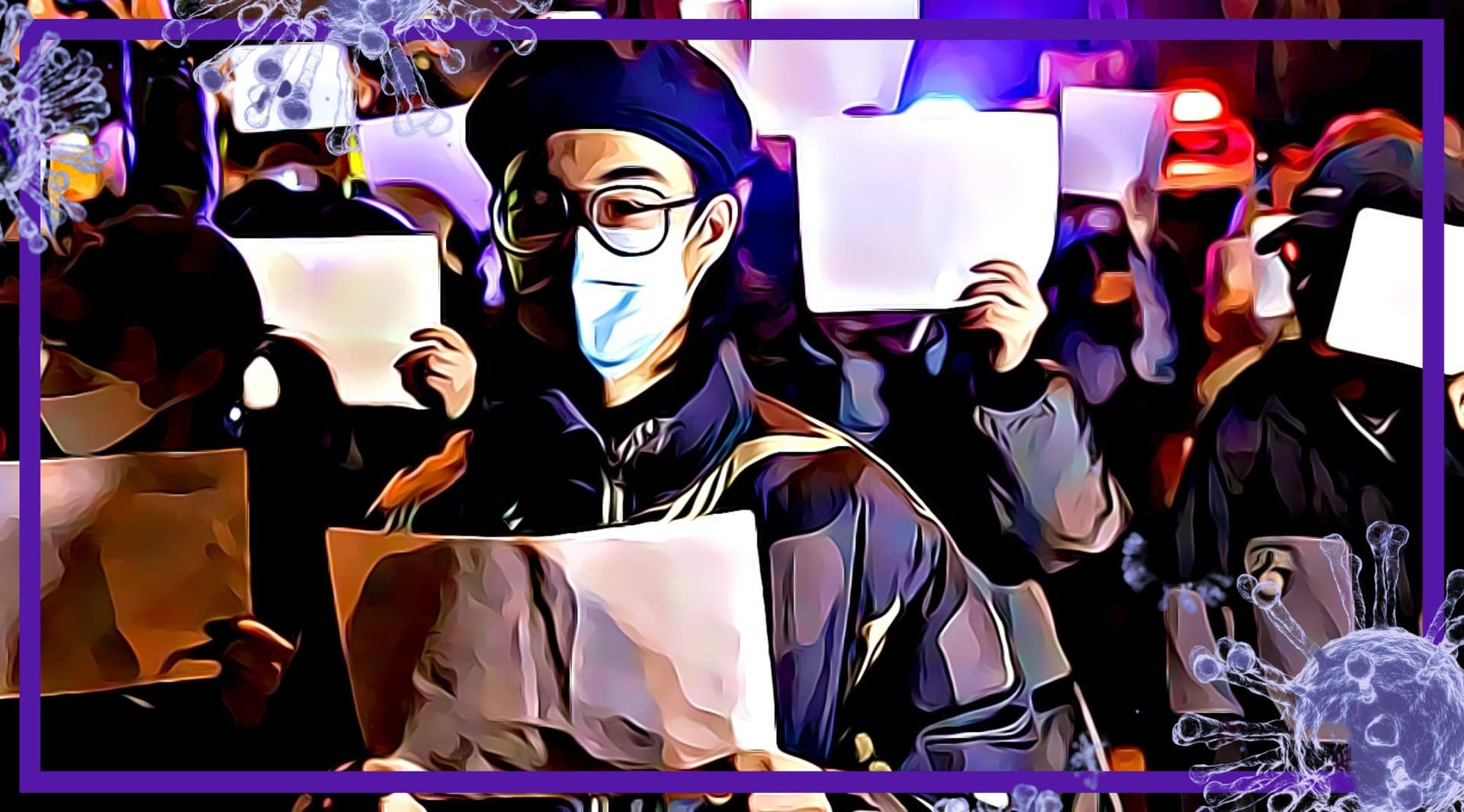

The government eased some of its strictest zero-Covid policies in early December. That followed a series of protests in major cities which included calls for leader Xi Jinping and the ruling Communist Party to step down. Protestors were able to protect their anonymity by holding up sheets of blank paper to symbolise state censorship in the so-called “A4 Revolution,” with some demanding “universal rights” and “freedom of expression.”

There is a “strong link” between the protests and the end of the zero-Covid policy, says Alfred Wu, associate professor at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore. The zero-Covid goal was always impossible due to the infectious nature of the illness, but the protests “accelerated” its dropping, he says.

Though it’s too soon to know if the protests will be a long-term turning point, Alfred Wu says that the authorities are worried about the risk that there may be more to come. “These protests can accelerate,” he says. “They could spread to wider contexts.”

Since the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, China’s population has accepted authoritarian control in return for the prospect of slowly rising living standards. Expectations about the future, Alfred Wu argues, are more important than absolute levels of current wealth. Inflation and high unemployment levels, which are understated in official statistics, are now undermining previously optimistic expectations, he says.

The government “used to rely on economic growth to boost its legitimacy,” Alfred Wu says. “It looked like a social contract.” That has changed due to Covid-19. “Security is now being moved up the agenda at the expense of economic growth.” He sees signs of a nostalgia in China for a “golden past” which has now been lost. Young people and private sector workers are “desperate. Everyone is suffering except the public sector.”

Fun Time?

Some fund managers are confident that China’s economy is about to benefit from a long-delayed return to economic activity. Jerry Wu, a fund manager at Polar Capital in London, sees a “strong reopening and recovery” to start with the Chinese New Year in late January. By the second quarter there should be a “vibrant, strong and booming economy” given three years of pent-up demand. Those who can afford to are “eager to travel, consume, and have fun.”

As an investment, China looks “very promising from a short to medium term perspective, as it is reopening, easing and entering a positive earnings cycle with very attractive valuation levels,” Jerry Wu argues.

A resumption of pre-Covid growth levels would bring its own problems for the government. China’s governance needs to evolve due to the “bottom up driver of the growth of the middle class,” says Jerry Wu. The number of people in China who meet a Western definition of “middle class” is between 150 million and 200 million, or about 20% of the adult population, he says. That leaves a lot of scope for increase, which will lead to “a stronger and vibrant civil society.”

Middle class aspirations are the major long-term domestic issue in China. The regime needs people to achieve middle class status at a steady pace – not too fast, which would make aspirations hard to control, and not too slow, which would cause too much discouragement. Even if this “Goldilocks” trick of social engineering can be pulled off, the problem is that many who have joined the Chinese middle class are now wishing they were somewhere else, with Chinese immigration consultants reporting a surge of interest this year.

Meanwhile, Chinese Internet discussions show that many young people are convinced that middle-class status is either impossible to achieve or not worth the effort. “Lying flat,” or accepting lower material prospects while taking it easy, was for a time a buzzword on Chinese social media. The more nihilistic “let it rot” came to prominence in 2022.

Economic Challenges

Dexter Roberts, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Indo-Pacific Security Initiative, argues that the main factors behind the zero-Covid policy shift were the “dire” state of the economy, the risk that local governments would run out of money, and government realisation that they were failing to stop the spread of the latest Covid variants.

“While the protests may have convinced Beijing to move faster to end the policy, that was only a matter of timing,” says Roberts, publisher of Trade War, a newsletter on the Chinese economy and business. “The regime already knew that the policy was unsustainable.”

China will continue to struggle with controlling Covid for at least the first quarter of 2023, which will disrupt manufacturing and supply chains, and continue to weigh heavily on consumption, Robert says. Coming from a low 2022 base, China is likely to see a surge in growth in 2023 that could easily top 5%, he predicts.

That “does not signal a healthy economy,” Roberts argues. The country continues to face huge challenges, including “lacklustre household consumption, destabilising debt, a rapidly aging population, and excessive government influence over the economy.”

According to research from Arup Raha, head of Asia atOxford Economics in December, a property sector bubble in some cities, continued trade friction with the US, and heightened political tensions mean that foreign capital is now demanding a higher risk premium. “China’s path to even a 4%-5% trend growth rate is likely to be a difficult one,” Raha writes.

‘Whole-process Democracy’

Like most authoritarian regimes, China has not felt confident enough to ditch the language of democracy. The government’s concept of “whole-process democracy” claims that rather than through Western-style elections, citizens get to have their say by submitting their opinions directly to the government through surveys. Whether or not such exercises have any democratic substance, the government wants its population to feel that they are being ruled with their consent and participation.

It’s possible that the protests simply reflected the fact that people could take no more as the rest of the world tried to get back to normal. Protests to date have mostly been driven by self-interest, rather than by cultural values, Alfred Wu says. Most recent protestors were simply frustrated at having been locked up for longer than people elsewhere, he adds.

Despite the mass dissent, which saw the global Chinese diaspora and the domestic population protesting together, the regime maintains its capability to control public discussion. “The propaganda machine is very strong,” says Alfred Wu, a former journalist in China.

People are now more likely to demand concessions from government and “may well push back against future government policies,” Robert says. Yet the government retains a strong capacity to resist demands that breach its red lines. “The full power of China’s surveillance state plus the enforcement capability of the public security forces can and will likely be used to squash future demonstrations against party policies,” he argues.

Still, the abrupt Covid policy shift has “badly damaged the population’s faith in the party, and likely does therefore mark a shift in the regime’s relationship with the people,” Roberts says. In future, people may be “far less likely to assume the party knows best when it comes to running the economy, society, and the political system.”

For now, Covid-19 remains the biggest problem, Alfred Wu says. The core of China’s failure to move on from Covid is that the country is unwilling to admit that its vaccines are much less effective than those used in the West. That failure, in many eyes, may have caused irreversible damage to the regime’s credibility. Alfred Wu suspects that most elderly Chinese would take foreign vaccines if they could get them. Low vaccination rates, he says, are linked to scepticism of Chinese products and the government which pushes them. “In reality there is resistance. People quietly distrust the government.”

David Whitehouse is a freelance journalist in Paris.

Author: David Whitehouse