The BIS (Bank of International Settlements) published a report on 23 June 2019 that sought to analyze the opportunities and risks that are posed as Big Tech moves into Financial activities. Below is the full report;

Key takeaways:

• The entry of large technology firms (“big techs”) into financial services holds the promise of efficiency gains and can enhance financial inclusion.

• Regulators need to ensure a level playing field between big techs and banks, taking into account big techs’ wide customer base, access to information and broad-ranging business models.

• Big techs’ entry presents new and complex trade-offs between financial stability, competition and data protection.

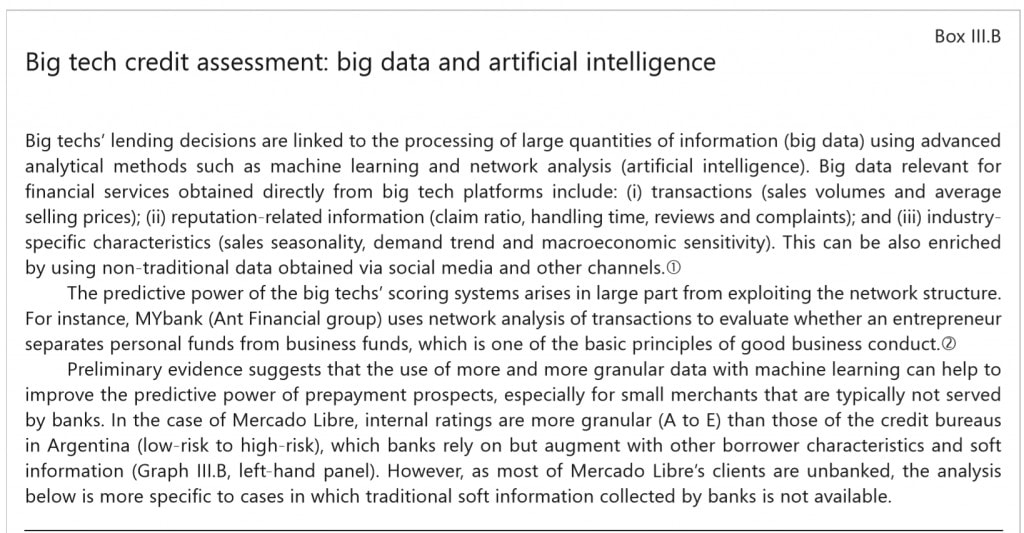

Technology firms such as Alibaba, Amazon, Facebook, Google and Tencent have grown rapidly over the last two decades. The business model of these “big techs” rests on enabling direct interactions among a large number of users. An essential by-product of their business is the large stock of user data which are utilized as input to offer a range of services that exploit natural network effects, generating further user activity. Increased user activity then completes the circle, as it generates yet more data.

Building on the advantages of the reinforcing nature of the data-network activities loop, some big techs have ventured into financial services, including payments, money management, insurance and lending. As yet, financial services are only a small part of their business globally. But given their size and customer reach, big techs’ entry into finance has the potential to spark rapid change in the industry. It offers many potential benefits. Big techs’ low-cost structure business can easily be scaled up to provide basic financial services, especially in places where a large part of the population remains unbanked. Using big data and analysis of the network structure in their established platforms, big techs can assess the riskiness of borrowers, reducing the need for collateral to assure repayment. As such, big techs stand to enhance the efficiency of financial services provision, promote financial inclusion and allow associated gains in economic activity.

At the same time, big techs’ entry into finance introduces new elements in the risk-benefit balance. Some are old issues of financial stability and consumer protection in new settings. In some settings, such as the payment system, big techs have the potential to loom large very quickly as systemically relevant financial institutions. Given the importance of the financial system as an essential public infrastructure, the activities of big techs are a matter of broader public interest that goes beyond the immediate circle of their users and stakeholders.

There are also important new and unfamiliar challenges that extend beyond the realm of financial regulation as traditionally conceived. Big techs have the potential to become dominant through the advantages afforded by the data-network activities loop, raising competition and data privacy issues. Public policy needs to build on a more comprehensive approach that draws on financial regulation, competition policy and data privacy regulation. The aim should be to respond to big techs’ entry into financial services so as to benefit from the gains while limiting the risks. As the operations of big techs straddle regulatory perimeters and geographical borders, coordination among authorities – national and international – is crucial.

Big techs in finance

The activities of big techs in finance are a special case of broader fintech innovation. Fintech refers to technology-enabled innovation in financial services, including the resulting new business models, applications, processes and products. While fintech companies are set up to operate primarily in financial services, big tech firms offer financial services as part of a much wider set of activities.

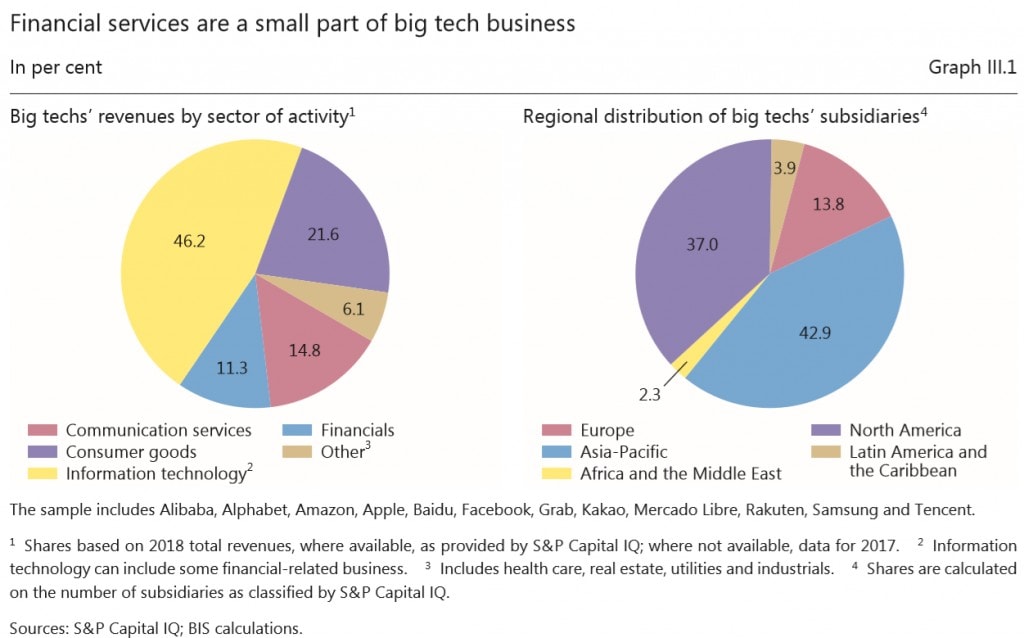

Big techs’ core businesses are in information technology and consulting

(eg cloud computing and data analysis), which account for around 46% of their revenues (Graph III.1, left-hand panel). Financial services represent about 11%. While big techs serve users globally, their operations are mainly located in Asia and the Pacific and North America (right-hand panel). Their move into financial services has been most extensive in China, but they have also been expanding rapidly in other emerging market economies (EMEs), notably in Southeast Asia, East Africa and Latin America.

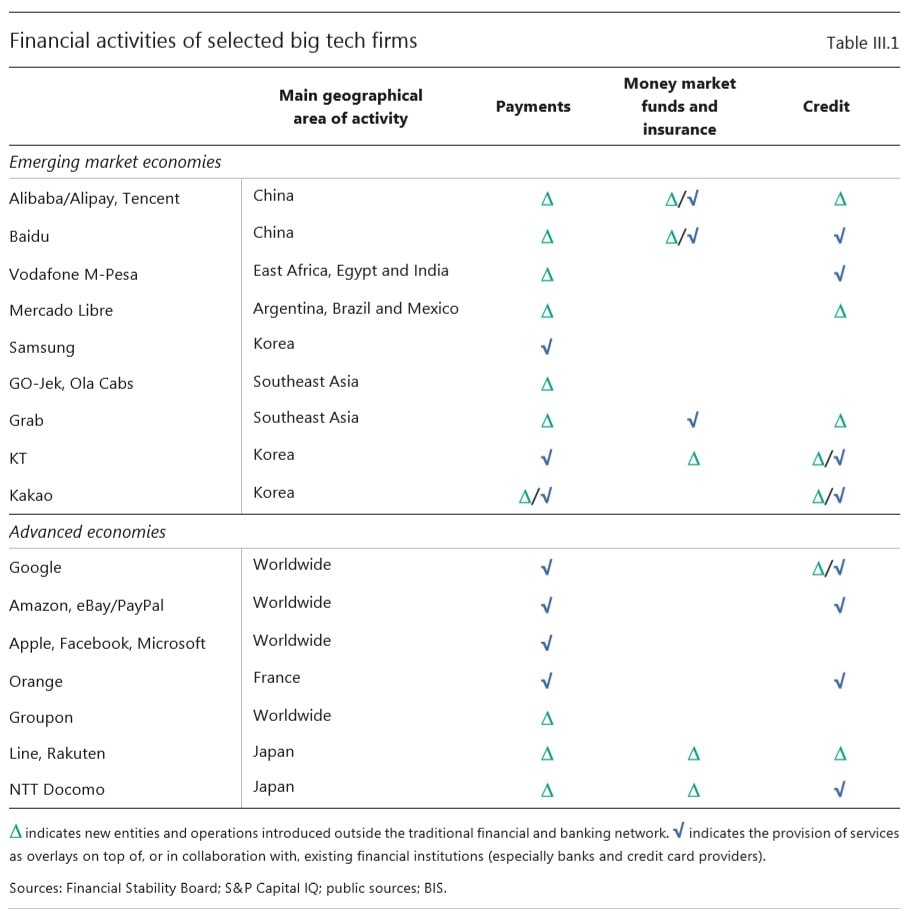

In offering financial services, big techs both compete and cooperate with banks (Table III.1). Thus far, they have focused on providing basic financial services to their large network of customers and have acted as a distribution channel for third-party providers, eg by offering wealth management or insurance products.

Payment services

Payments were the first financial service big techs offered, mainly to help overcome the lack of trust between buyers and sellers on e-commerce platforms. Buyers want delivery of goods, but sellers are only willing to deliver after being assured of payment. Payment services like those provided by Alipay (owned by Alibaba) or PayPal (owned by eBay) allow guaranteed settlement at delivery and/or reclaims by buyers and are fully integrated into e-commerce platforms. In some regions with less developed retail payment systems, new payment services emerged through mobile network operators (eg M-Pesa in several African countries). Over time, big techs’ payment services have become more widely used as an alternative to other electronic payment means such as credit and debit cards.

Big techs’ payment platforms currently are of two distinct types. In the first type, the “overlay” system, users rely on existing third-party infrastructures, such as credit card or retail payment systems, to process and settle payments (eg Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal). In the second, users can make payments which are processed and settled on a system proprietary to the big tech (eg Alipay, M-Pesa, WePay).

While big techs’ payment platforms compete with those provided by banks, they still largely depend on banks. In the first type, directly so; in the second, users require a bank account or a credit/debit card to channel money into and out of the network. Big techs then hold the money they receive in their own regular bank accounts and transfer it back to users’ bank accounts when users request repayment. To settle between banks, big techs have to again use banks, since they do not participate in regular interbank payment systems for the settlement in central bank money.

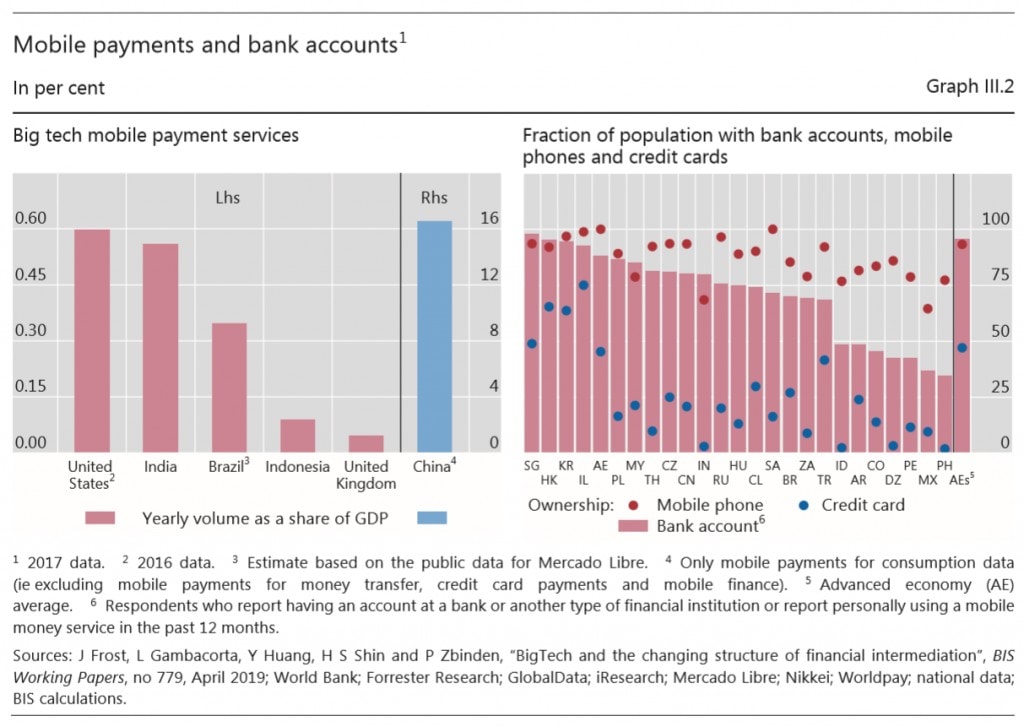

Overlay systems are used more commonly in the United States and other advanced economies since there credit cards were already ubiquitous by the time e-commerce firms such as Amazon and eBay came to prominence. Proprietary payment systems are more prevalent in jurisdictions where the penetration of other cashless means of payment, including credit cards, is low. This helps explain the large volume of big tech payment services in China: 16% of GDP, dwarfing that elsewhere (Graph III.2, left-hand panel).

More generally, big techs have made greater inroads where the provision of payments is limited and mobile phone penetration high. For instance, as a large fraction of the population in EMEs remains unbanked (Graph III.2, right-hand panel), the high mobile phone ownership rate has allowed digital delivery of essential financial services, including cashless payments, to previously unbanked households and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Remittance services, and cross-border retail payments more broadly, are another activity ripe for entry. Current services are often costly and slow, and it is difficult for senders to verify receipt of funds. Some big techs have started to offer (near) real-time transfers at relatively low cost. Examples include the remittance service between Hong Kong SAR and the Philippines offered by Alipay HK (a joint venture of Ant Financial and CK Hutchison) and GCash (operated by Globe Telecom). These cross-border transactions, however, still rely on a correspondent banking network and require collaboration with banks. Other big techs (eg Facebook) are reportedly considering offering payment services for their customers on a global basis.

Money market funds and insurance products

Big techs use their wide customer network and brand name recognition to offer money market funds and insurance products on their platforms. This business line capitalizes on big techs’ payment services. Big techs’ one-stop shops aim to be more accessible, faster and more user-friendly than those offered by banks and other financial institutions.

On big tech payment platforms, customers often maintain a balance in their accounts. To put these funds to use, big techs offer money market funds (MMFs) as short-term investments. The MMF products offered are either managed by companies affiliated with the big tech firm or by third parties. By analyzing their customers’ investment and withdrawal patterns, big techs can closely manage the MMFs’ liquidity. This allows them to offer users the possibility to invest (and withdraw) their funds almost instantaneously.

In China, MMFs offered through big tech platforms have grown substantially since their inception (Graph III.3, left-hand panel). Within five years, the Yu’ebao money market fund offered to Alipay users grew into the world’s largest MMF, with assets over CNY 1 trillion (USD 150 billion) and around 350 million customers.

Despite their rapid growth, MMFs affiliated with big techs in China are still relatively small compared with other savings vehicles. At end-2018, total MMF balances related to big techs amounted to CNY 2.4 trillion (USD 360 billion), only about 1% of bank customer deposits or 8% of outstanding wealth management products.

The expansion of big tech MMFs in China and in other countries has benefited from favourable market conditions. For example, the launch of Yu’ebao coincided with interbank interest rates exceeding deposit rates, allowing big techs to offer higher rates. As rates declined recently, Yu’ebao’s assets stopped growing and even saw reductions (Graph III.3, centre panel). Similarly, PayPal closed its MMF in 2011, after interest rates in the United States fell to close to zero (right-hand panel).

Some big techs have started to offer insurance products. Again, they use their platforms mainly as a distribution channel for third-party products, including auto, household liability and health insurance. In the process, they collect customer data, which they can combine with other data to help insurers improve their marketing and pricing strategies.

Credit provision

Building on their e-commerce platforms, some big techs have ventured into lending, mainly to SMEs and consumers. Loans offered are typically credit lines, or small loans with short maturity (up to one year). The (relative) size of big tech credit varies greatly across countries. While total fintech (including big tech) credit per capita is relatively high in China, Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States, big techs account for most fintech credit in Argentina and Korea (Graph III.4).

The uneven expansion of total fintech credit appears to reflect differences in economic growth and financial market structure. Specifically, the higher a country’s per capita income and the less competitive its banking system, the larger total fintech credit activity. The big tech credit component has expanded more strongly than other fintech credit in those jurisdictions with lighter financial regulation and higher banking sector concentration.

Despite its substantial recent growth, total fintech credit still constitutes a very small proportion of overall credit. Even in China, with the highest amount of fintech credit per capita, the total flow of fintech credit amounted to less than 3% of total credit outstanding to the non-bank sector in 2017.

Big techs’ relatively small lending footprint so far has reflected their limited ability to fund themselves through retail deposits. Big techs have some options to overcome this constraint.

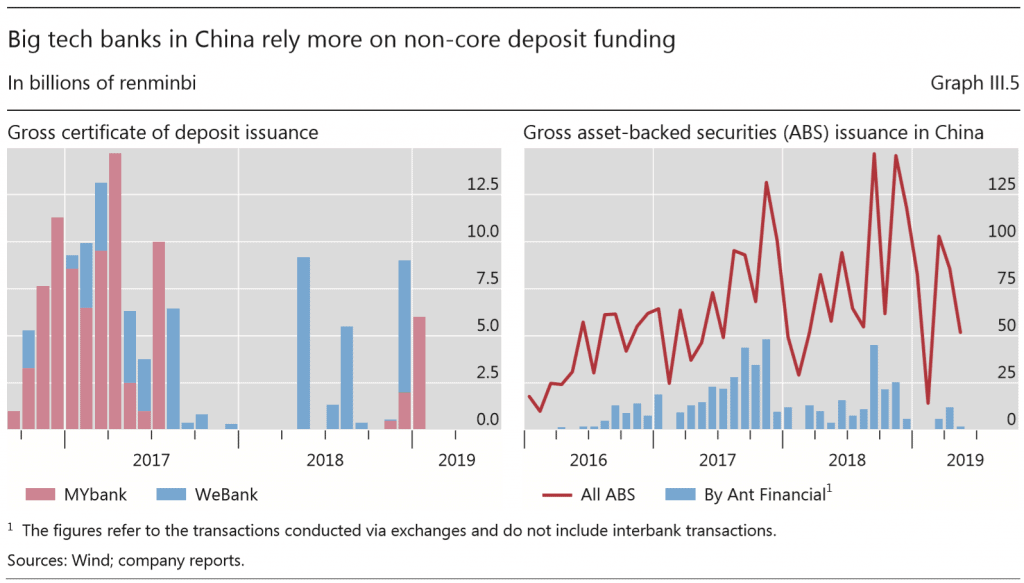

One is to establish an online bank. But in some countries, regulatory authorities restrict the opening of remote (online) bank accounts. One example is China, where the two Chinese big tech banks (MYbank and WeBank) rely mostly on the interbank market funding and certificates of deposit (Graph III.5, left-hand panel) rather than on traditional deposits. More recently, however, these banks have started to issue “smart deposits” that offer significantly higher interest rates than other time deposits and the possibility of early withdrawal at a reduced rate.

A second option is to partner with a bank. Big techs can provide the customer interface and allow for quick loan approval using advanced data analytics; if approved, the bank is left to raise funds and manage the loan. This option can be attractive to big techs as their platforms are easily scalable at low cost and they interface directly with the client. It may also be profitable for banks, as they can gain an extra return – despite providing lower value added services.

A third option is to obtain funds through loan syndication or securitization – already a common strategy among fintech firms. For instance, Ant Financial’s gross issuance of exchange-traded asset-backed securities (ABS) accounted for almost one third of the total securitization in China in 2017 (Graph III.5, right-hand panel).

Why do big techs expand into financial services?

Big techs have typically entered financial services once they have secured an established customer base and brand recognition. Their entry into finance reflects strong complementarities between financial services and their core non-financial activities, and the associated economies of scope and scale.

The DNA of big techs

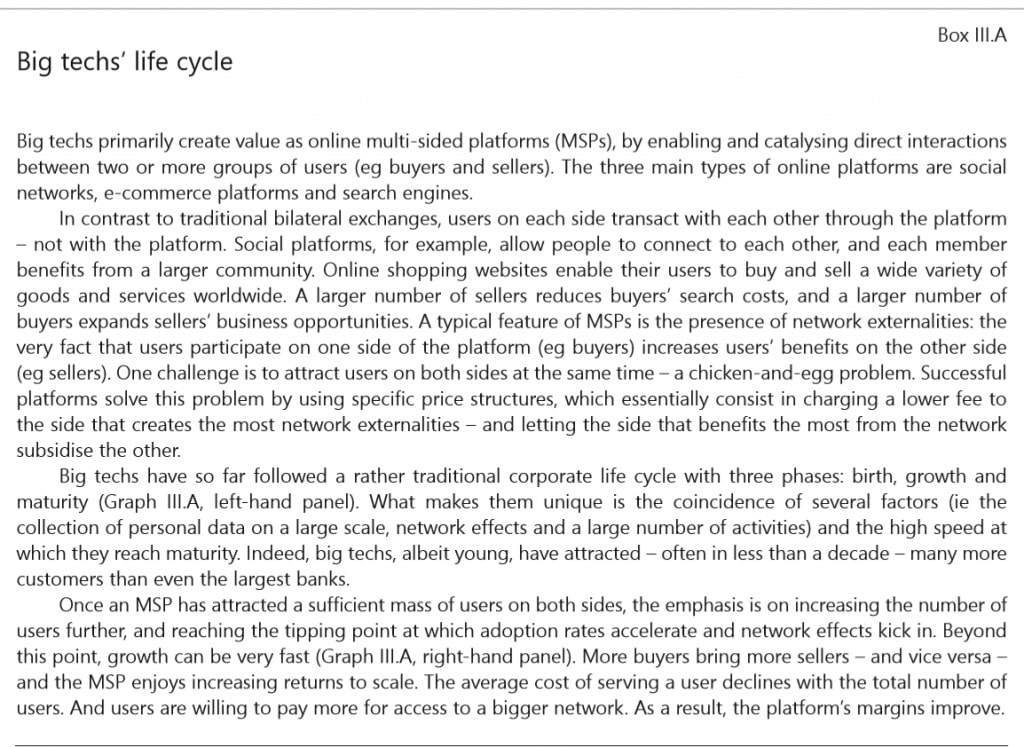

Data analytics, network externalities and interwoven activities (“DNA”) constitute the key features of big techs’ business models. These three elements reinforce each other. The “network externalities” of a big tech’s platform relate to the fact that a user’s benefit from participating on one side of a platform (eg as a seller on an e-commerce platform) increases with the number of users on the other side (eg buyers). Network externalities beget more users and more value for users. They allow the big tech to generate more data, the key input into data analytics. The analysis of large troves of data enhances existing services and attracts further users. More users, in turn, provide the critical mass of customers to offer a wider range of activities, which yield even more data. Accordingly, network externalities are stronger on platforms that offer a broader range of services, and represent an essential element in big techs’ life cycle (Box III.A).

Financial services both benefit from and fuel the DNA feedback loop. Offering financial services can complement and reinforce big techs’ commercial activities. The typical example is payment services, which facilitate secure transactions on e-commerce platforms, or make it possible to send money to other users on social media platforms. Payment transactions also generate data detailing the network of links between fund senders and recipients. These data can be used both to enhance existing (eg targeted advertising) and other financial services, such as credit scoring.

The source and type of data and the related DNA synergies vary across big tech platforms. Those with a dominant presence in e-commerce collect data from vendors, such as sales and profits, combining financial and consumer habit information. Big techs with a focus on social media have data on individuals and their preferences, as well as their network of connections. Big techs with search engines do not observe connections directly, but typically have a broad base of users and can infer their preferences from their online searches.

The type of synergies varies with the nature of the data collected. Data from e-commerce platforms can be a valuable input into credit scoring models, especially for SME and consumer loans. Big techs with a large user base in social media or internet search can use the information on users’ preferences to market, distribute and price third-party financial services (eg insurance).

Although large banks have many customers and offer a wide range of services too (eg distribution of wealth management or insurance products, mortgages), so far they have not been as effective as big techs at harnessing the DNA feedback loop. Payments aside, banks have not exploited activities with strong network externalities. One reason is the required separation of banking and commerce in most jurisdictions. As a result, banks have access mostly to account transaction data only. Moreover, legacy IT systems are not easily linked to various other services through, for instance, application programming interfaces (APIs). Combining their advanced technology with richer data and a stronger customer focus, big techs have been adept at developing and marketing new products and services. The main competitive advantages and disadvantages of large banks versus big techs are summarised in Table III.2.

Big techs’ impact on financial services

Big techs’ DNA can lower the barriers to provision of financial services by reducing information and transaction costs, and thereby enhance financial inclusion. However, these gains vary by financial service and could come with new risks and market failures.

Big techs’ potential benefits in lending activities

Besides the cost of raising funds, the cost of lending is closely tied to the ex ante evaluation of credit risk and the ex post enforcement of loan repayments. To price loans, banks must assess the riskiness of their borrowers, typically by gathering information from various sources and building close relationships. To incentivise borrowers to repay their loans and limit losses in case of default, banks monitor borrowers or require collateral. As all this is costly and time-consuming, banks require a compensation in the form of fees or interest rate spreads. Big techs’ access to and use of big data for screening and monitoring borrowers’ activity reduce such costs, which can improve efficiency and broaden access to financing.

Screening and financial inclusion

The information cost may sometimes be so prohibitive that banks refrain from serving borrowers – or do so only at very high spreads. This is true regardless of whether the information is soft (communicated but difficult to quantify) or hard (quantitative data that can be easily processed). Most at risk from exclusion are borrowers who lack basic documentation or are difficult to reach, eg because they are too remote geographically. For instance, many SMEs in developing economies do not meet the minimum requirements for a formal bank loan application, as they often do not have audited financial statements.

As a result, big techs can have a competitive advantage over banks and serve firms and households that otherwise would remain unbanked (Graph III.6, left-hand panel). They do so by tapping different but relevant information through their digital platforms. For example, Ant Financial and Mercado Libre claim that their credit quality assessment and granting of loans typically involve more than 1,000 data series per loan applicant.

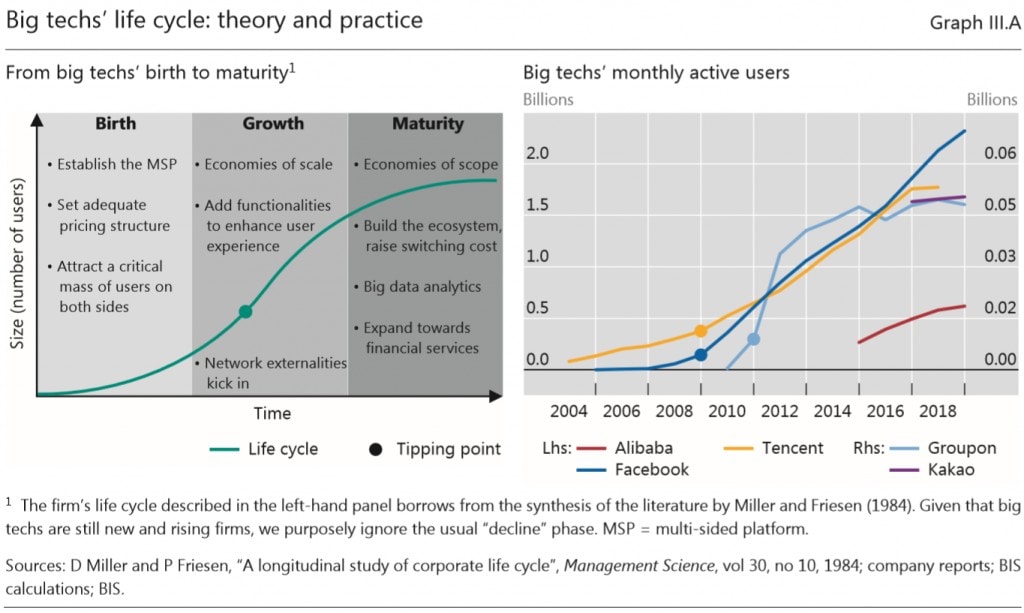

Recent BIS empirical research also suggests that big techs’ credit scoring applied to small vendors outperforms models based on credit bureau ratings and traditional borrower characteristics (Box III.B). All this could represent a significant advance in financial inclusion and help improve firms’ performance.10 Although the preliminary evidence is encouraging, it is still early to draw definitive conclusions on the quality of those risk assessments. Most have been applied to very specific forms of credit (eg small business credit lines), the comparisons do not include the soft information available to banks and performance has not been tested through full business and financial cycles.

Monitoring and collateral

The cost of enforcing loan repayments is an important component of total financial intermediation cost. To reduce enforcement problems banks usually require borrowers to pledge tangible assets, such as real estate, as collateral to increase recovery rates in the case of default. Another mean is monitoring. Banks spend time and resources monitoring their clients’ projects to limit the risk that borrowers implement them differently from what was agreed initially. Through monitoring, firms and financial intermediaries also develop long-term relationships and build mutual trust, which makes defaulting less attractive for borrowers.

Big techs can address these issues differently. When a borrower is closely integrated in an e-commerce platform, for example, it may be relatively easy for a big tech to deduct the (monthly) payments on a credit line from the borrower’s revenues that transit through its payment account. In contrast, banks may not be in the position to do so as the borrower can have accounts with other banks. Given network effects and high switching costs, big techs could also enforce loan repayments by the simple threat of a downgrade or an exclusion from their ecosystem if in default. Anecdotal evidence from Argentina and China suggests that the combination of massive amounts of data and network effects may allow big techs to mitigate information and incentive problems traditionally addressed through the posting of collateral. This could explain why, unlike banks’, big techs’ supply of corporate loans does not closely correlate with asset prices (Graph III.6, right-hand panel).

Big techs’ potential costs: market power and misuse of data

Big techs’ role in financial services brings efficiency gains and lowers barriers to the provision of financial services, but the very features that bring benefits also have the potential to generate new risks and costs associated with market power. Once a captive ecosystem is established, potential competitors have little scope to build rival platforms. Dominant platforms can consolidate their position by raising entry barriers. They can exploit their market power and network externalities to increase user switching costs or exclude potential competitors. Indeed, over time big techs have positioned their platforms as “bottlenecks” for a host of services. Platforms now often serve as essential selling infrastructures for financial service providers, while at the same time big techs compete with these providers. Big techs could favour their own products and try to obtain higher margins by making financial institutions’ access to prospective clients via their platforms more costly. Other anticompetitive practices could include “product bundling” and cross-subsidizing activities. Given their business model, these practices could reach a larger scale for big techs.

Another, newer type of risk is the anticompetitive use of data. Given their scale and technology, big techs have the ability to collect massive amounts of data at near zero cost. This gives rise to “digital monopolies” or “data-opolies”. Once their dominant position in data is established, big techs can engage in price discrimination and extract rents. They may use their data not only to assess a potential borrower’s creditworthiness, but also to identify the highest rate the borrower would be willing to pay for a loan or the highest premium a client would pay for insurance. Price discrimination does not just have distributional effects, i.e. raising big techs’ profits at customers’ expense without changing the overall amounts produced and consumed. It could also have adverse economic and welfare effects. The use of personal data could lead to the exclusion of high-risk groups from socially desirable insurance markets. There are also some signs that big techs’ sophisticated algorithms used to process personal data could develop biases towards minorities.

The idea that people’s preferences are malleable and are subject to influence for commercial gain is not new. But the scope for such actions may be greater in the case of big techs, due to their command over much richer customer information and their integration into their customers’ everyday life. Anecdotal evidence indeed suggests that big techs may be able to influence users’ sentiment without the users themselves being aware of it.

Public policy towards big techs in finance

Traditionally, financial regulation is aimed at ensuring the solvency of individual financial institutions and the soundness of the financial system as a whole. It also incorporates consumer protection goals. The policy instruments used to achieve these goals are well understood, ranging from capital and liquidity requirements in the case of banks to the regulation of conduct for consumer protection. When big techs’ activity falls squarely within the scope of traditional financial regulation, the same principles should apply to them.

However, two additional features make the formulation of the policy response more challenging for big techs. First, big techs’ activity in finance may warrant a more comprehensive approach that encompasses not only financial regulation but also competition and data privacy objectives. Second, even when the policy goals are well articulated, the specific policy tools should actually be shown to promote those objectives. This link between ends and means should not be taken for granted. This is because the mapping between policy tools and the ultimate welfare outcomes is more complex in the case of big techs. In particular, the policy tools that are aimed at traditional financial regulation objectives may also impinge on competition and data privacy objectives, and vice versa. These interactions introduce potentially complex trade-offs that do not figure in traditional financial regulation. Each of these issues is explored in turn.

“Same activity, same regulation”

A well functioning financial system is a critical public infrastructure, and banks occupy a central place in that system through their role in the payment system and in credit intermediation. Banks’ soundness is a matter of broader public interest beyond the narrow group of direct stakeholders (their owners and creditors). For this reason, banks are subject to regulations that govern their activities, and market entry is subject to strict licensing requirements. Likewise, when big techs engage in banking activities, they are rightfully subject to the same regulations that apply to banks. The aim is to close the regulatory gaps between big techs and regulated financial institutions so as to limit the scope for regulatory arbitrage through shadow banking activities. Accordingly, regulators have extended existing banking regulations to big techs. Examples include the extension of know-your-customer (KYC) rules – designed to prevent money laundering and other financial crimes – to big techs’ operations in payments. The basic principle is “same activity, same regulation”. If big techs engage in activities that are effectively identical to those performed by banks, then such activities should be subject to banking rules.

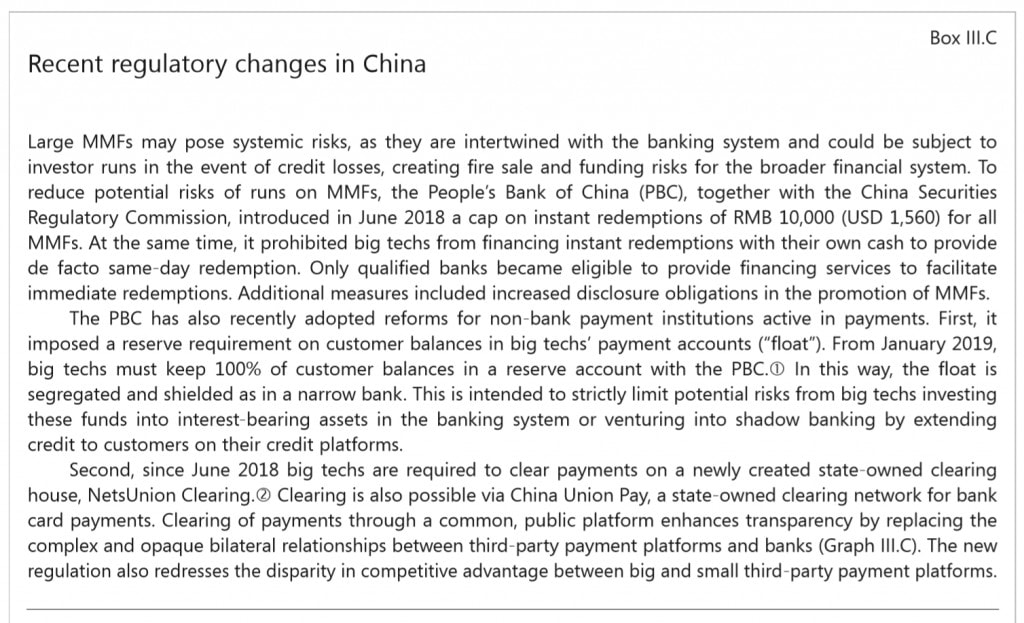

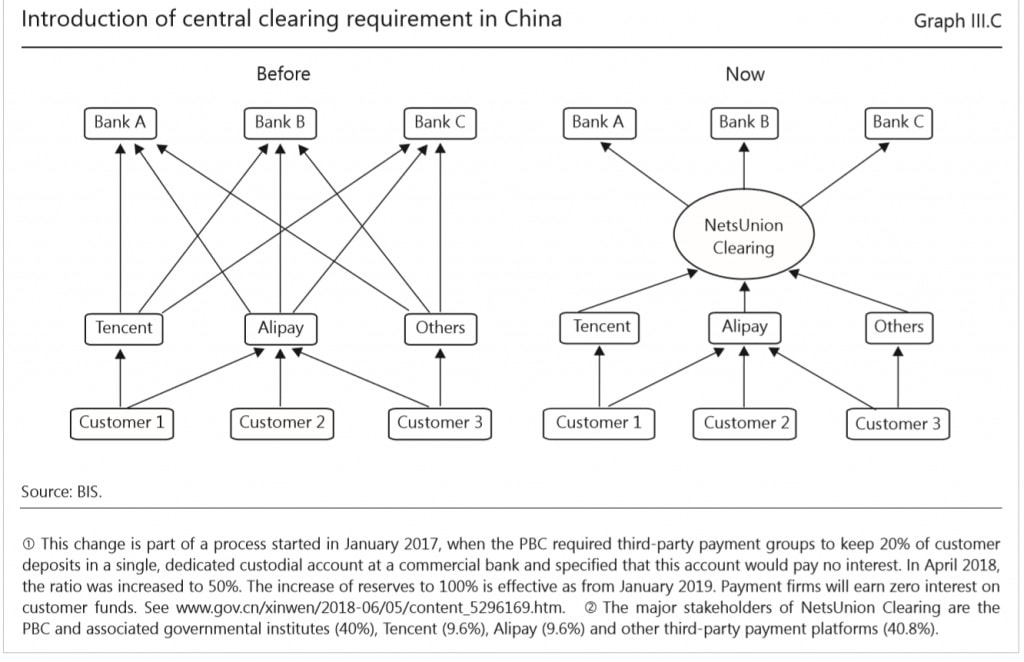

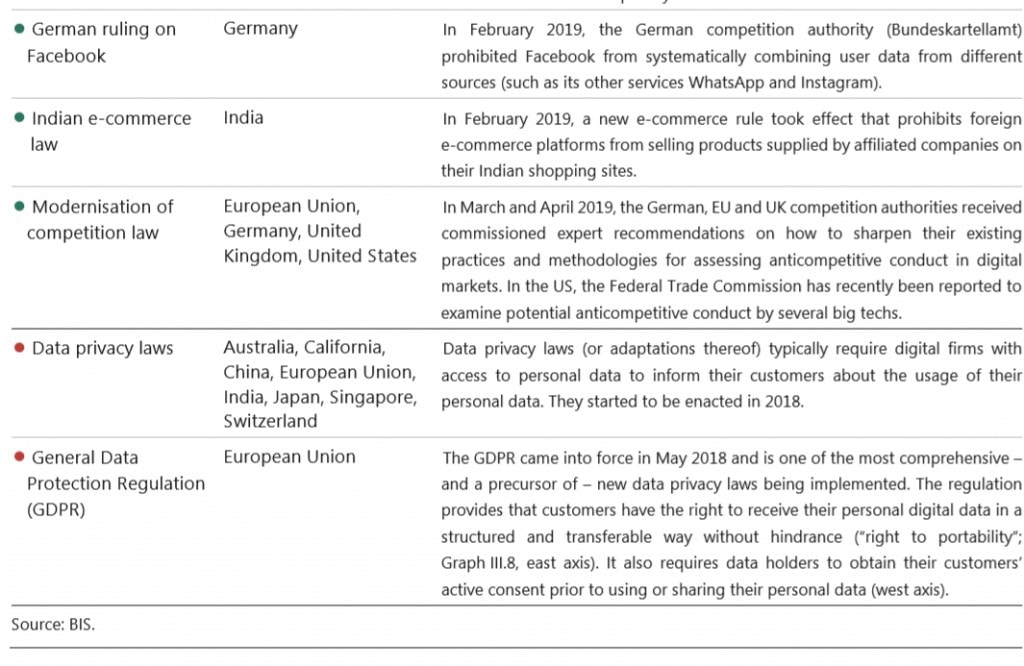

arranted in those cases where big techs have wrought structural changes that take them outside the scope of existing financial regulation. Prudential regulators have turned their attention to specific market segments, notably in the payment system, where big techs may have already become relevant from a systemic perspective. Where rapid structural change has outrun the existing letter of the regulations, a revamp of those regulations will be necessary. The general guide is to follow the risk-based principle and adapt the regulatory toolkit in a proportionate way. In China, for instance, big techs’ sizeable MMF businesses play an important role for interbank funding. These MMFs mainly invest in unsecured bank deposits and reverse repos with banks. The rapid structural change has introduced new linkages in the financial system. Around half of MMFs’ assets are bank deposits and interbank loans with a maturity of less than 30 days. A risk is thus that a redemption shock to big techs’ MMF platforms quickly transmits to the banking system through deposit withdrawals. Another concern is the systemic nature of the payment links when banks are reliant on funding from payment firms. To address these risks, the authorities in China have introduced new rules requiring settlement on a common, public platform for all payment firms, as well as on redemptions and the use of customer balances (Box III.C).

A new regulatory compass

When the objectives of policy extend beyond the goals of traditional financial regulation into competition and data privacy, new challenges present themselves. Even when the objectives are clear and uncontroversial, selecting the policy tools to secure the objectives – the means towards the ends – requires taking account of potentially complex interactions.

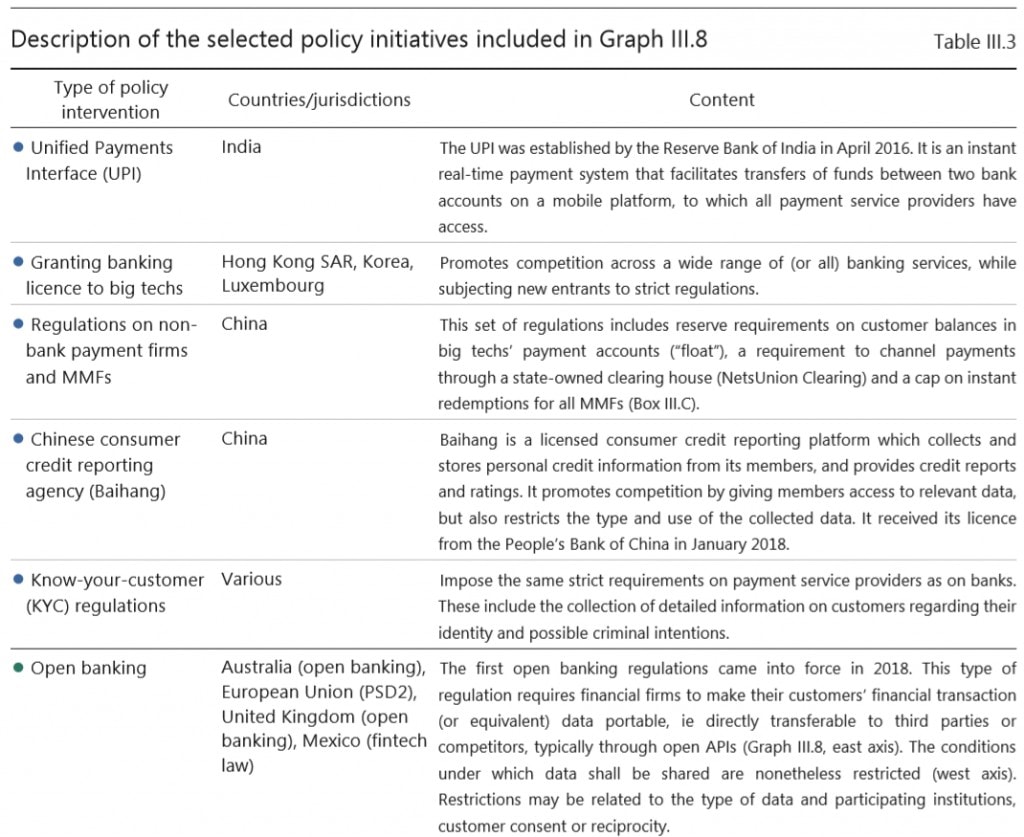

To navigate the new, uncharted waters, regulators need a compass that can orient the choice of potential policy tools. These tools can be organised along the two dimensions, or axes, of a “regulatory compass” (Graph III.8). The north-south axis of the compass spans the range of choices over how much new entry of big techs into finance is encouraged or permitted. North indicates encouragement of new entry, while south indicates strict restrictions on entry. The second dimension in the compass spans choices over how data are treated in the regulatory approach. It ranges from a decentralised approach that endows property rights over data to customers (east), to a restrictive approach that places walls and limits on big techs’ use of such data (west).

Current practices cover a broad territory spanned by the two axes. These practices are represented as dots in this space. The placement of the dots reflects the multifaceted nature of the policy choices in that components of the approaches can be placed in different places on the compass. The choices also involve decisions by three types of official actors: financial regulators (blue dots), competition authorities (green dots) and data protection authorities (red dots). As can be seen in Graph III.8, the choice of policy tools has been quite heterogeneous across jurisdictions (Table III.3).

The regulatory compass reflects the menu of policy choices, not the outcomes as measured against the ultimate goals. The evaluation of the policy choices according to their effectiveness in achieving the ultimate objectives would require the further step of analyzing the mapping from the policy tools to the ultimate outcomes. This final step is far from simple given the complex interactions between the objectives of solvency, competition and data privacy. Nevertheless, the regulatory compass helps to organize thinking and sheds light on this mapping between means and ends.

Revisiting the competition–financial stability nexus

Take the concrete example of the interplay between competition objectives and financial stability objectives. Traditionally, public policy on entry into the banking industry has been influenced by two divergent schools of thought on the desirability of competition in banking. One view is that the entry of new firms in the banking sector is desirable as it fosters competition and reduces incumbents’ market power. The associated policy prescription is to foster new firms’ entry in the banking industry by operating a liberal policy on issuing banking licences. Regulators may also lower entry costs in some specific market segments, especially where the scope for technological progress is the greatest. In India, for instance, they have favoured the development of the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which gives authorised mobile payment providers, including big techs, access to the interbank payment system.

On the other side of the debate is the school of thought emphasising that a concentrated – or less competitive – banking sector is desirable because it is conducive to financial stability. Incumbents are more profitable – and thus more able to accumulate a strong equity base – and have a higher franchise value – and are thus more likely to act prudently. Moreover, they may have access to more stable (insured) funding bases. The associated policy approach is to restrict new entry by maintaining strict licensing requirements for new entrants. In the regulatory compass, the degree of stringency in allowing big techs’ entry is spanned by the north-south axis, with north being the policy of being permissive towards new entry while south is the policy of restricting entry.

However, the relationship between entry and effective competition is far from obvious when the DNA feedback loop is taken into account. New entry may not increase market contestability – and competition – when big techs are envisaged as the new entrants. This is because big techs can establish and entrench their market power through their control of key digital platforms, eg e-commerce, search or social networking. On the one hand, such control may generate outright conflicts of interest and reduce competition when both big techs and their competitors (eg banks) rely on these platforms for their financial services. On the other hand, a big tech could be small in financial services and yet rapidly establish a dominant position by leveraging its vast network of users and associated network effects. In this way, the rule of thumb that encouraging new entry is conducive to greater competition can be turned on its head.

The traditional focus of competition authorities on a single market, firm size, pricing and concentration as indicators of contestability is not well suited to the case of big techs in finance. Just as the mapping between policy choices to outcomes can be complex for financial regulators, competition authorities may also need to adapt their paradigms. As part of this effort, some jurisdictions (eg the European Union, Germany, India, the United Kingdom and the United States) have recently been upgrading their rules and methodologies for assessing anticompetitive conduct.23 In India, for example, the main e-commerce platforms are prohibited from selling products supplied by affiliated companies on their websites to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

The new competition–data nexus

By tying market power to the extensive use of customer data, big techs’ DNA feedback loop creates a new nexus between competition and data.

Abstracting from privacy concerns, wide access to data can in principle be beneficial. Digital data are a non-rival good – ie they can be used by many, including competitors, without loss of content. Moreover, since data are obtained at zero marginal cost as a by-product of big techs’ services, it would be socially desirable to share them freely. Provided that markets are competitive, open access to data can help to lower the switching costs for customers, alleviate hold-up problems and generally foster competition and financial inclusion.

The issue, therefore, is how to promote data-sharing. Currently, data ownership is rarely clearly assigned. For practical purposes, the default outcome is that big techs have de facto ownership of customer data, and customers cannot (easily) grant competitors access to their relevant information. This uneven playing field between customers and service providers can be remedied somewhat by assigning data property rights to the customers. Customers could then decide with which providers to share or sell data. In effect, this attempts to resolve inefficiencies through the allocation of property rights and the creation of a competitive market for data – the decentralised or “Coasian” solution. The east-west axis of the regulatory compass maps out the range of choices according to the degree to which authorities rely on allocating property rights to data versus outright restrictions on the data’s use. The further east one travels, the greater the emphasis on the decentralised solution based on data portability and data property rights.

However, the mapping between the policy tools and the ultimate outcomes is more complex in the case of big techs. The DNA feedback loop challenges a smooth application of the Coasian approach. The reason is twofold. First, big techs can obtain additional data from their own ecosystems (social networking, search, e-commerce, etc), outside the financial services they operate. Second, data have increasing returns to scope and scale26 – a single additional piece of data (eg a credit score) has more value when combined with an existing large stock of data – and economies of scope – eg when used in the supply of a broader range of services. For both reasons, data have more value to big techs. In a bidding market for data, big techs would most likely outbid their competitors. Letting market forces freely run their course could not be guaranteed to result in the desired (competitive) outcomes. Concretely, if banks’ customers were to grant (or sell) big techs unrestricted access to their banking data, this could reinforce the DNA feedback loop and paradoxically increase big techs’ competitive advantage over banks, as opposed to keeping it in check.

Given the network effects underlying competition, the competitive playing field may be levelled out more effectively by placing well designed limits on the use of data. Introducing some additional rules regarding privacy – while at the same time allowing selectively for the sharing of some types of data – could increase effective competition, because the addition of such limitations on the use of data could curb big techs’ exploitation of network externalities.

This policy choice along the data usage dimension – as represented by the east-west axis of the regulatory compass in Graph III.8 – has taken centre stage in the debate on big techs. The underlying arguments that bear on the available choices are reflected in the policies recently adopted in a number of jurisdictions. Two particular examples are the various forms of open banking regulations that have been adopted around the world, and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Open banking regulations give authorized third-party financial service providers direct access to bank customer data and – in some cases – banks reciprocal access to third parties’ equivalent data. They also set common technical standards for APIs, but do not give customers as much control over their personal data as the GDPR. To the extent that they entail the transfer of data ownership from big techs to customers, both regulations can be seen as measures intended to facilitate greater effective market contestability. For this reason, they are positioned in the northeast quadrant in Graph III.8. Data portability allows customers to transfer personal data easily across different services and for their own purposes. As such, it is an important step towards defining the terms of competition in the financial sector.

At the same time, some of the new regulations also limit the scope of datasharing. Regulations that circumscribe the use of data are positioned in the western half of the compass. The rationale for limiting the use of data rests on a number of considerations. For one, not all types of data are relevant for the provision of financial services. To assess a borrower’s creditworthiness, for example, a lender may not necessarily need to know their social habits or travel plans. Moreover, not all types of service providers should be given access to their customers’ financial data. In any case, there are more fundamental considerations from privacy for limits on the use of personal data. Accordingly, open banking regulations selectively restrict the range of data that can be transmitted (eg financial transaction data), as well as the type of institutions among which such data can be shared (eg accredited deposit-taking institutions). Similarly, the GDPR requires customers’ active consent before a firm can use their personal data. Both types of restrictions can be seen as barriers to big techs’ entry into finance. For this reason, they are positioned in the southwest quadrant of the compass. More drastic approaches involve outright restrictions on the processing of user data. One example of a policy initiative that aims at levelling the competitive playing field by limiting the use of data is the recent rule by Germany’s competition authority that prohibits a prominent social network from combining its user data with those it collects from its affiliated websites and applications. Where to draw the line is an issue that involves not just economics, but also society’s privacy preferences.

The regulatory compass is a useful device to classify the range of policy initiatives that impinge on the use of data and market entry. However, it remains to be seen how far these policy initiatives will lead to the desired outcomes in terms of effective competition, efficiency and soundness of the financial system. A broadening of perspectives will be essential to make considered policy choices in this area.

Policy coordination and need for learning

In the face of the rapid and global digitisation of the economy, policymakers need institutional mechanisms to stay abreast of developments and to learn from and coordinate with each other.

Some countries have set up innovation facilitators. These can take a number of forms, including hubs and accelerators, which provide a forum for knowledgesharing, and may involve active collaboration or even funding for new players. Regulatory sandboxes (eg in Hong Kong, Singapore and the United Kingdom) let innovators test their products under regulatory oversight. Hubs, accelerators and sandboxes can help to ensure a dynamic financial landscape – one that is not necessarily dominated by just a few players. At the same time, their setup requires careful design and implementation, to avoid regulatory arbitrage and to not provide signs of support for new but still speculative projects.

Coordination among authorities is crucial, at both the national and the international level. First, there is a need for coordination of national public policies.

The mandates and practices of the three different national authorities – competition authorities, financial regulators and data protection supervisors – may not always be compatible. Financial regulators focus on the specifics of the financial sector, whereas competition and data privacy laws often impose general standards that apply to a wide range of businesses. Second, as the digital economy expands across borders, there is a need for international coordination of rules and standards (eg for data exchange). To prevent those differences from leading to conflicting actions, policymakers not only need a new compass but also need to find the right balance of public policy tools.

9 Responses